Fool’s Gold and Diamonds in the Rough: The Adolescent Growth Spurt in Boys

/This article is Part 5 in a multi-part series on Long-Term Athlete Development, or LTAD. Be sure to check out Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 , and Part 4 for more information on LTAD!

The stories that you are about to read are true accounts of human growth and maturation and its implications for youth sports. Names have been changed to protect the innocent.

Big Sam and Little Jimmy: Fool’s Gold and a Diamond in the Rough

Do you remember Sam, that big, early maturing boy who shaved in sixth grade? You know, the six-footer who stood under the basketball hoop and scored at will, and struck everybody out in baseball?

But Big Sam barely grew another inch. So, as a high school senior he played guard, but because he always played in the post as a youth, he couldn’t dribble very well. He didn’t even start—and actually came off the bench averaging just 2.8 points per game as a high school senior. By the way, he also quit baseball because he got frustrated that everyone caught up to his 68 mph fastball that was “blazing” in Little League…but not so much at 60’6”!

And what about little Jimmy—that short, scrawny kid who loved playing sports but got out-muscled in basketball (but could beat everyone in H-O-R-S-E), and although he had a great swing, couldn’t hit it out of the infield in baseball? Do you remember when Jimmy finally hit his growth spurt and grew into his body as a junior and averaged 12.3 points per game as a senior. Oh, by the way, he went onto a great college baseball career.

Yeah, I remember both Sam and Jimmy. And I continue to see this scenario play out in youth sports as a coach and pediatric exercise scientist. I actually see the former case more so than the latter, merely because the late maturing boy, or “late bloomer,” is too often selected out of (excluded) sports that require size, speed, and strength: football, baseball, hockey, and basketball.

“Fool’s gold is valuable to those who are impatient.”

Growth, Maturation, Talent ID and Athlete Development

First, the terms “growth” and “maturation” are often used interchangeably—sort of like how people will also interchange the measurement or research concepts of reliability and validity when talking about data or studies: they are related by separate constructs. Growth can be defined as an increase in size of the whole body and its parts. All systems, including organs and tissues, grow during childhood and adolescence. One visible expression of this growth is the change in height.

As the body grows, it also matures biologically—that is, it progresses toward the mature state. A key concept of maturation is that it varies in its timing (when do certain key events occur) and tempo (what is the progress or rate between key events).

In boys, there are a few outward signs of biological maturation: facial and armpit hair, voice change, and B-O (body odor!). The bones are growing and also changing shape, working towards the fusion of the growth plate. And, there are changes in the secondary sex characteristics as well.

Biological maturity can be assessed from the secondary sex characteristics and skeletal age of a hand-wrist x-ray, but both methods are invasive. Thus, we will focus on somatic (height) assessment of biological maturity.

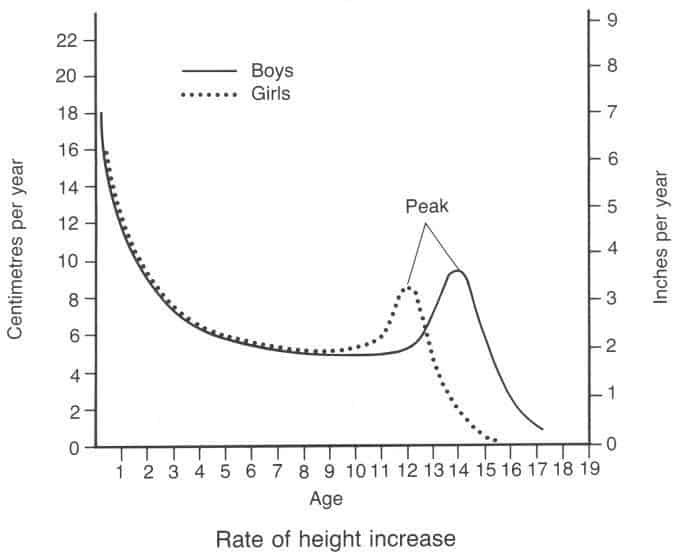

Obviously, a key period in human growth and maturation is adolescence and puberty and its marked growth spurt. The hallmark event of the growth spurt—the age at peak height velocity (APHV)—can be used to classify individuals as early, average or late maturers.

Determining Maturity Status: Early, Average or Late?

If one has recorded height from roughly the age of 9 years through 16 years, the APHV can be determined (see figure above). Data from U.S. indicates that APHV occurs at about age 13.8 years in boys. So, we can classify the maturity groups as follows:

Early Maturer APHV<12.8 years

Average Maturer APHV 12.8-14.8 (13.8 years +/- 1 year)

Late Maturer APHV >14.8 years

However, this method requires routine measurements over time (every 3-6 months), and many coaches, parents and athletes want to know now.

Are there any other methods to detect it or predict it sooner? Yes, the Mirwald equation (also called the maturity offset) and the Khamis-Roche method only require a snapshot of measurements.

The Khamis-Roche method does not specifically calculate the APHV, but instead estimates adult height. The current height is then expressed as a percentage of the predicted adult height, which in turn can be matched to corresponding events during the growth spurt to provide an indication of maturity status as follows:

Pre-growth spurt (<85%)

Pre-PHV/early phase of growth spurt (85-89%)

Mid-late growth spurt (89-95%)

Post-growth spurt (>95%)

Thus, if the same-aged boys are assessed we could determine which ones are more or less advanced in maturity (e.g., closer to mature adult height).

Implications of Maturity Status on Youth Sports: Talent ID and Selection

We all can probably recall the early maturing boy who “fizzled out” and the late bloomer who sprouted up and starred. There are many implications for maturity status on youth sports including competitions, training, injury risk, participation, etc.

Think about the tryout process in youth sports. Let’s say 40 kids show up for 12 roster spots on a U12 baseball team. The coaches watch the boys stroll in and quickly note the big kids (i.e., social stimulus effect). They continue to focus their attention towards them throughout the tryout and note how hard this kid throws and hits the ball—irrespective of his technique or coachability. On the other hand, the smaller, weaker boy who possesses a good understanding of the game and great footwork and hands in the infield (yet struggles to throw it hard) gets discarded because “well, he’s too small.” Has this coach selected the Fool’s Gold at the top of the pile? And didn’t dig deep enough for the Diamond in the Rough? And, is the focus on winning the U12 championship, or player development?

Currently in the big four sports for males, there is a preference for earlier maturers, especially during the middle school years (11-14 years). The advantages for these youngsters include: greater encouragement, more playing time, preference for important positions, and better coaching and training opportunities and resources. On the other hand, the late bloomer of equal technical and tactical skill will either be overlooked or excluded.

So, what can a coach do?

Educate coaches, parents, and youngsters on this matter. Pass along this blog to them.

Routine measurement of height and weight along with additional variables to predict adult stature.

During tryouts, note the maturity groups by armband or jersey color.

Index physical attributes like strength, speed and power by maturity group rather than chronological age.

Keep talented late maturers in the system and foster their development.

Introduce “biobanding” into training and competitions. Biobanding is the grouping of individuals by maturity status instead of age. This concept will be covered in depth in a future blog.

“Give fools their gold, and knaves their power; let fortune’s bubbles rise and fall;

who sows a field, or trains a flower, or plants a tree, is more than all.”

Join hundreds of thousands of coaches and athletes using Volt's intelligent training system. For more information, click here.

Learn more about Dr. Eisenmann | @Joe_Eisenmann