Bulletproof Your Squat by Eliminating These 5 Errors

/Ah, the squat. The bread-and-butter staple of nearly every strength training program (including Volt). A movement as simple as sitting down or getting up from a chair, and yet complex: how wide should your stance be? How low should your hips sink? Where should your knees track? We work with athletes from age 14 all the way up to the pro level, so I've compiled a list of the top 5 squat errors we see the most—and tips to fix them!—to help you squat better (and heavier).

1. Knees Moving Forward

When your knees move forward during your squat descent, it usually indicates a more quad-dominant movement pattern. Most athletes will feel their heels begin to lift up off the floor as their knees deviate too far anteriorly—but some athletes possess enough calf and heel mobility to keep their heels planted, even as their knees travel forward.

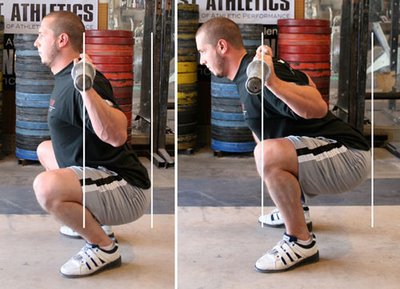

Left: a "high-bar" squat, which places more emphasis on the anterior chain (especially quadriceps. Right: a "low-bar" squat, which loads the hips and hamstrings first and places less stress on the knees.

During the squat, you can place more tension on specific muscle groups by making small tweaks to your form. As Kelly Starrett, DPT, states in his popular text Becoming a Supple Leopard, “the tissues and joints that get loaded first during movement get loaded maximally during movement”—in other words, that which gets loaded first gets loaded most. If you initiate a squat by bending your knees first, your knees will be loaded most as you lower into the squat. This, as you can imagine, places huge strain on the knee joint (especially the patellar tendon and anterior cruciate ligament [ACL]) by calling on the quadriceps to do the most work during the squat.

If you load your hips first, however, it’s a different story: the large muscle groups of your glutes and hamstrings take the brunt of the load, in a much more mechanically efficient movement. If you notice your knees shifting forward as you squat, use the coaching cues “hips back” and “shins vertical” to help you recruit the posterior chain in the movement. Also look at where you are resting the bar on your upper back: too high, and it might be causing you to bring your knees forward as you descend.

2. Knees Caving In

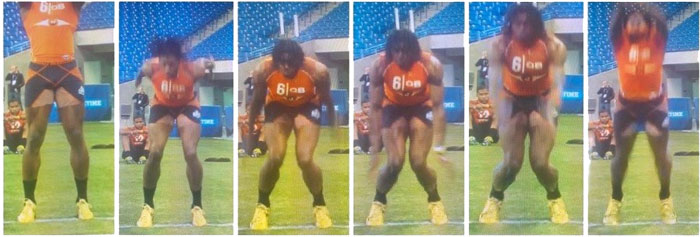

Knees caving in during squatting (and jumping and landing) can put the knees at greater risk for injury.

I’ve written about valgus knee collapse before, in my controversial article about NFL quarterback Robert Griffin III (nicknamed RG3) and his history of lower extremity injuries. Essentially, if your knees cave inward during your squat—either during the descent or the ascent phase—you are putting your knee joint in an unstable and unsafe position. This is sometimes called knee valgus, valgus collapse, or some combination of the two. And women, unfortunately, run a greater risk of knee injury from valgus collapse due to our larger hip-to-knee angle (Q angle).

But valgus collapse doesn’t only affect women. If you have tight or weak hips and glutes—especially your gluteus medius, the glute muscle that abducts the leg—you may notice your knees caving inward during your squat. This creates extra strain on your quadriceps muscles and puts the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) at the front of your knee in what we might call a biomechanically untenable position.

Nope.

If you do notice your knees caving in, use the coaching cues “knees out” or “spread the floor” (with your feet) to recruit the lateral glute muscles and put your body in a more advantageous—and safer—position. You can also try looping a band around your legs just above or below the knee joint to help “cue” your glutes to take action to help your knees track properly. (*Note: we do not recommend shoving your knees outward as far as possible, but rather using that mental cue to help you recruit the muscles that keep your knees in a structurally sound position under load.)

3. Heels Coming Up

If your heels come up off the floor as you squat, you may be leaning too far forward or squatting too narrow.

Do you rise up onto your toes at the bottom of your squat? If so, this may indicate that you are leaning too far forward (potentially from a weak core or too-heavy load) or using a stance that is too narrow for your body. Keeping your heels down during the squat—and especially “driving” through your heels as you ascend—is crucial for recruiting your posterior chain during the movement. Makes sense: driving through your heels uses the back of your body; driving through the balls of your feet uses your quads (and knees) only.

If you find yourself falling forward during your squat, your bar may be too heavy. It can be challenging for some athletes to maintain a braced and neutral spine during a bodyweight squat, let alone maximal loads. In this sense, your “core” (muscles surrounding your trunk on all sides) can truly be a limiting factor in your back squat 1RM. As your torso leans forward, your center of gravity likewise shifts forward, pulling you up onto your toes to compensate. Think “core locked,” “shoulders back,” and “chest proud” to help keep your torso upright as you squat.

Coming up onto the toes may also indicate that your stance is too narrow, curbing the contribution from your glutes and hamstrings and placing the load solely on your quadriceps. (You may also notice your knees shifting forward, too.) Try widening your stance to help recruit the glutes and hams—feet just outside the shoulders is usually a good starting place for most athletes.

Also, use the cue “heels down” or “drive through the heels” to help keep your heels firmly planted as you ascend.

4. Not Reaching Full Depth (Hips Parallel or Below Knees)

Your body is designed to squat deeper than this.

If your hips never reach a parallel plane to your knees, your squat is too shallow. Depending on your hip mobility, the length of your femurs, and the way your femurs are situated within your hip socket, you should be able to reach at least a parallel thigh position, if not much deeper.

Squatting is arguably one of the very best full-body exercises for building structural strength and power. So why short-change this million-dollar movement by only reaching half-depth? If you want functional strength—the kind of strength that translates to better movement patterns and athletic performance—you need to move within your body’s full range of motion (ROM). Otherwise, you’re only strengthening specific segments of the muscles involved.

If your hips aren’t sink to knee-level or lower, try lightening your load. A too-heavy bar may cause you to abbreviate the movement to avoid a failed attempt. Another trick: start with a Box Squat. The Box Squat is a fantastic movement for teaching correct hip-hinge mechanics (which help prevent knees moving forward) and gaining confidence in the movement. Then, starting with light weight, practice deepening the movement, keeping your knees wide to engage your hips in positions of deeper flexion. Filming yourself—or asking a friend to do it for you—is a good way to see how low your hips are sinking. You may not be going as deep as you think!

Make sure you reach full depth — hips parallel or below the knees.

5. Rounding the Back

If you find yourself excessively rounding your upper back or exaggerating the arch in your lower back during a squat, you’re putting your spine in a seriously unstable position. The shear forces on your vertebrae created by loading an unstable spine can lead to some nasty disc injuries or nagging back pain. The best position for your spine during a squat is neutral: maintaining the slight curve of your mid-upper spine and the slight arch of your lower spine, reinforced with engaged core muscles.

Superman is a great exercise for building posterior chain strength and awareness along the muscles of your spinal column.

If your back rounds forward during the squat, you may have tight hamstrings. Tight and weak hamstrings often correlate to back pain, and can be an early indicator of hamstring injury—never fun. Make sure your hamstrings (on both legs) have enough ROM to safely complete the squat (lying on your back, you should be able to bring each leg to 90 degrees without the knee bending). You also may have difficulty activating the muscles of your mid-upper spine, causing you to round forward under load. Try strengthening your mid-upper back with exercises like Superman, to help you feel what it’s like to activate the strong cords of muscle that run along your spine and create carryover to your squat.

If your lower back is doing the rounding, you may have to work on your core control (specifically where the trunk muscles connect to your pelvis) and/or look at the anterior hip. If your quads and hip flexors are brutally tight, this can cause you to compensate for their lack of ROM by tilting your pelvis forward as you descend (“duck butt”). Try strengthening and stabilizing your core with exercises like Planks or Band Anti-Rotations—and make sure your quads and hip flexors possess enough ROM to complete the movement safely.

The Takeaway

The bottom line here is this: the human body was designed to squat, and squat efficiently. There is not "one squat fits all" form—but if you're noticing major errors in your squat form, or experiencing pain during your squats, you can fix it! The first step to fixing your squat is always to lighten your load. It is better to do 10 bodyweight squats with perfect form than 100 heavy squats with poor form. Practicing good form with lighter loads will help your brain make those important neuromuscular adaptations that will translate when you load up your bar. Make your bodyweight squats perfect first—and the rest will follow. Happy squatting!

Join over 1 Million coaches and athletes using Volt's intelligent training app. For more information, click here.

Learn more about Christye and read her other posts | @CoachChristye