Life in the NBA: Damaged Goods and Youth Training Habits

/In my previous article on the NBA Combine, I focused on the predictability of the athletic tests (speed, agility, vertical jump, etc.) performed at the NBA Combine on future on-court performance. In this follow-up article, I want to consider another facet of the journey to the NBA—and, if you make it there, life in the NBA.

What am I talking about? It’s that dreaded word in the sports world: injury. Not only do I want to address the injury epidemic in the NBA, but also relate it back to the early training habits of the youth hoopster. And even if your sport isn’t basketball, many of these lessons apply to the entire youth sports landscape as well.

The Grind

Life in the NBA is a 9- to 10-month grind (or longer), and this has trickled down to the youth level as well. (More on that later.) For now, let’s consider the impact of the schedule, travel, and on-court demands that has perhaps contributed to the injury epidemic that has plagued the NBA.

If you are not aware of it, this should get your attention: did you know that the economic impact of injuries in the NBA equals $350,000,000 per year?! If you are like me and not used to this type of dollar figure, you might have problems counting zeros across all those commas—but that’s right folks: 350 MILLION dollars! And season after season, a key factor in the playoffs is which starters are healthiest.

Several articles have been written on the injury bug in the NBA, and of course this has also gotten the attention of the league office as well. In an effort to address health and safety, the National Basketball Players Association hired a Director of Sports Medicine and Research.

Missed Opportunities

In some cases, talented players never get their chance in the NBA. Prospective players have seen their stock drop upon examining their injury history and medical test results at the NBA Combine. Meanwhile, other talented players suffer career ending injuries in college or even high school. Who wants damaged goods? If you’re paying top dollar for goods or services then you want your money’s worth, right? Or if you have a $60,000 race car, take care of it!

Is it possible that the NBA injury epidemic goes beyond the crowded schedule and is related to what happened during youth basketball? I’ve heard from several college strength and conditioning coaches that the 18-year-old athletes coming into college are already damaged goods. They also comment on how ill-prepared they are to participate in the rigors of a systematic strength and conditioning program.

Long-Term Athlete Development chart. Image via Canadian Sport for Life.

Is LTAD the Solution?

Can we blame part of the “damaged goods” condition of 18- to 25-year-old basketball players on the high mileage without an oil change, tire rotation, or tune-up that occurred in youth basketball? The sports specialization and year-round play in youth sports is no secret and many youth basketball players compete year-round on school and/or travel teams coupled with local pick-up games, practices, and private training sessions designed to “accelerate” the development of a blue-chip scholarship player. This has created a culture of over-competition and undertraining (that includes a lack of focus on fundamental basketball skills and general athletic development). It is not uncommon for youth and high school-aged hoopsters to play multiple games in a day during tournament play—but it IS uncommon for them to be seen in the weight room!

Are Basketball Players Allergic to the Weight Room?

My personal observations and experiences plus discussions with coaches leads me to state that few young basketball players participate in a well-designed strength and conditioning program. Indeed, it’s no secret that many young basketball players shy away from the weight room. They love to work on their game—shooting 3’s or working on one-on-one moves. But mention lifting weights, and you might get “No thanks, I don’t want to get big arms. It will mess up my shot.”

Now, there is a chance that you might be able to convince them to work on lower-body strength and power (squats and plyometrics) to improve their “bounce” (i.e., vertical jump)—IF they have any legs left from the pick-up games and weekend tourneys. This is why college strength coaches say they are ill-prepared for the rigors of the college training environment, and it may also be a reason for injuries at the next level.

A final note on physical preparation. Let’s not forget about the warm-up. For a lot of athletes, and not just basketball players, there is simply not enough attention paid to a proper dynamic warm-up. For some basketball athletes, a warm-up means you grab the ball, dribble it for a few minutes, and then start shooting. Maybe toss in a quick arm-across-the-chest stretch, or foot-to-butt stretch, and shake it out. Yep, ready to go! Just imagine how different this scenario could be: a 10- to 15-minute integrated neuromuscular dynamic warm-up that consists of a microdosing of fundamental athletic movements, balance, coordination, etc., performed 2-3 times per week has been shown to reduce the likelihood of injury in adolescent athletes.

LTAD Efforts by USA Basketball and the NBA

In recognition of the global issues in youth sports that were also permeating into its own sport, USA Basketball and the NBA established three expert working groups: 1) Health and Wellness, 2) Rules and Playing Standards, and 3) Curriculum and Instruction. The product, summarized below, has helped shaped LTAD and coach education with the aim of positively impacting the 37.5 million youth ages 6-18 who participate in basketball and also those who go onto play, coach or officiate collegiately, professionally and recreationally as adults.

In October 2016, the first-ever youth basketball guidelines aimed at improving the way children, parents, and coaches experience the game were released. This information (and there is a lot of it) is available on the USA Basketball, NBA and Jr. NBA websites. However, it can be challenging to navigate and interpret, so I’ve tried to consolidate and synthesize for you here.

Basketball Player Development

Similar to the approach of other national governing bodies, the Balyi LTAD model discussed in a previous blog served as the basis for the USA Basketball Player Development model. The model consists of a progressive Player Development Curriculum across four levels—Introductory, Foundational, Advanced, and Performance—for 3- to 18+-year olds. The Jr. NBA also utilizes a four-level approach, but focuses on elementary- and middle school-aged youth (6- to 14-year-olds).

The USA Basketball levels are summarized below and are underpinned by the general principles of LTAD along with the basketball-specific technical and tactical skills of Ball Handling & Dribbling, Footwork & Body Control, Passing & Receiving, Rebounding, Screening, Shooting, Team Defensive Concepts & Team Offensive Concepts. Both USA Basketball and the Jr. NBA provide excellent resources through a skills and drill video library along with comprehensive practice plans (resources at the end of blog).

The Introductory Level is designed for youngsters 3 to 9 years of age who have just started playing the game. For preschoolers, this may be the toy hoop or dribbling in the driveway. At the start of elementary school, the focus should be upon learning fundamental movement skills and building overall motor skills with ball handling and dribbling being of paramount importance, since these two skills allow the basketball to be advanced up and down the court. Shooting is also introduced at a hoop of lower height. Youngsters are also introduced to team concepts along with group skill competitions. However, it is strongly recommended that 5x5 competition be avoided until fundamentals are developed. It is also important to note that participation in basketball is recommended for only once or twice per week with daily participation in other sport activity the remainder of the week (i.e., sport sampling and building the “movement alphabet”).

The Foundational Level is for youngsters 8 to 13 years of age who have some experience but need to continue focusing upon fundamental movement skills and individual basketball-specific skills (dribbling, passing, shooting, etc.) about 70% of the time. From a team perspective, position concepts are taught, but coaches should not assign player positions at any point in the level. The remaining 30% of the time can be spent on actual game competition including small-sided play (1x1, 2x2, 3x3, skill games) and actual 5x5 play; however, it is recommended that 5x5 competition not be the focus until later in the level.

The Advanced Level is for youngsters 12 to 17 years of age who play on travel, middle school, or high school teams. At this level, more emphasis begins to be placed on strength and conditioning activities to build the aerobic base and also increase strength, while continuing to further develop overall basketball skills (“build the engine and consolidate basketball skills”). Early in the level (approx. age 12 to 14), 60% of the time should be spent on individual training and 40% spent on competition, including 5x5 play and small-sided games (1x1, 2x2, 3x3, skill games) as well as team-oriented practices. Later in the level (approx. age 15 to 17) and depending on mastery of skills, the switch can be made to a 50:50 training to competition ratio and players can specialize in a position.

The Performance Level is for high performing high school aged (15 to 18+ years old) competitors with the aim of maximizing fitness, individual position-specific skills, and competition preparation (i.e., optimize the engine of skills and performance). The training to competition ratio in this phase shifts to 25:75, understanding that the competition percentage includes team-oriented practices and other competition-specific preparations.

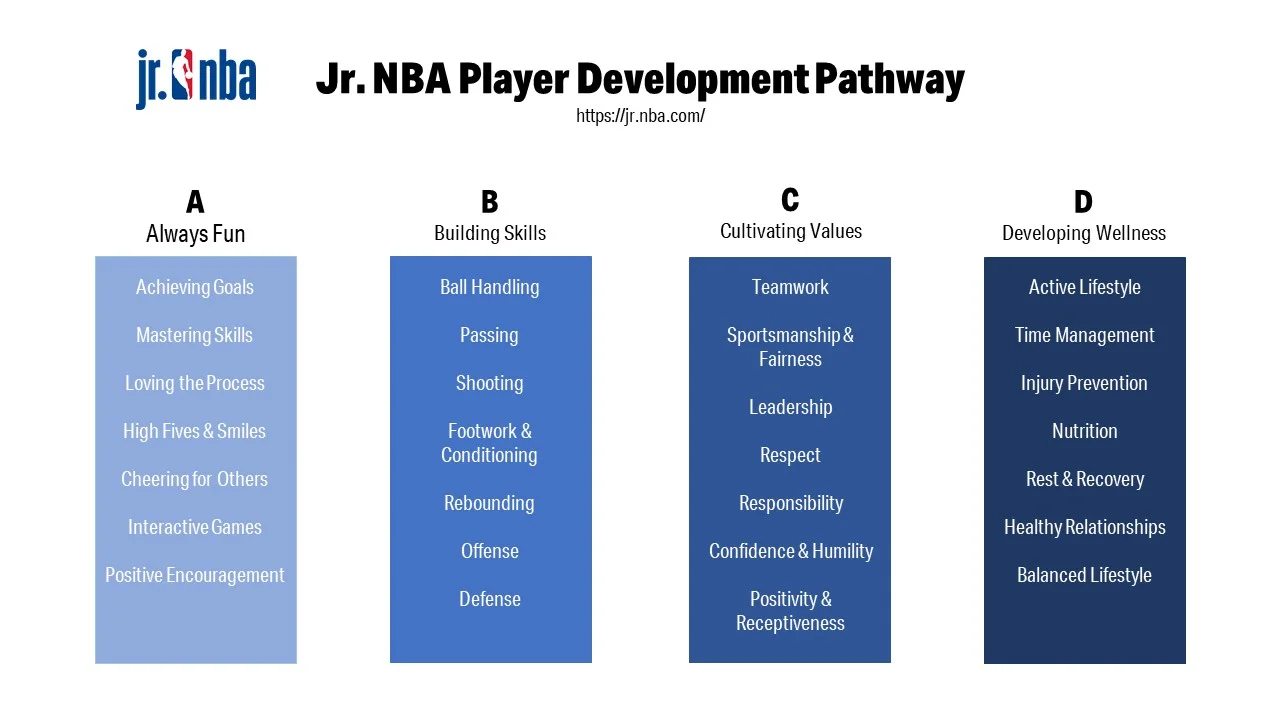

The ABCD's of the Jr. NBA's youth development pathway.

Let’s take a short side note here to cover the Jr. NBA Pathway, which focuses on ages 6 to 14 years and provides overlap to the first two levels of the USA Basketball model described above. The four levels—Rookie, Starter, All Star, and MVP—are based on skill proficiency rather than age. The ABCD’s of the Jr. NBA are the foundation of the instructional curriculum that includes a comprehensive video library of 250 skills and drills along with practice plans (12 practice plans per level, 48 total) and a skills checklist for each level.

Developmentally Appropriate Game Modifications

Remember shooting at that 10-foot hoop with the big ball as a 9-year-old? Or running all the way down the full-length court? Wait, sometimes you didn’t even make two dribbles because the other team was full-court pressing!

Developing confidence and competence at younger ages requires rule and game modifications, which is just what the expert working group on Playing Standards at USA Basketball did in four key areas aligned to an age/grade player segmentation structure. For details on the developmentally appropriate playing standards and rules, refer to their website.

Equipment & Court Specifications (e.g., proper height of the basket, size of the ball, and court dimensions and lines)

Game Structure (e.g., length of the game, scoring and timeouts

Game Tactics (e.g., equal playing time, player-to-player vs. zone defense, pressing vs. no pressing)

Game Play Rules (e.g., use of a shot clock, substitutions, clock stoppage)

Player Health and Well-being

As previously mentioned, overscheduling of competitive events, early specialization, overuse injuries and burnout have become too common in youth basketball. The Health and Wellness working group proposed eight recommendations for promoting a positive and healthy youth basketball experience.

Promote personal engagement in youth basketball and other sports.

Youth sports should include both organized and informal, peer-led activities.

Youth should participate in a variety of sports.

Delay single-sport specialization in the sport of basketball until age 14 or older.

Ensure rest from organized basketball at least one day per week, and extended time away from organized basketball each year.

Limit high-density scheduling based on age-appropriate guidelines.

Further evaluation of basketball-specific neuromuscular injury prevention training program is warranted.

Parents and coaches should be educated regarding concepts of sport readiness and injury prevention.

The Race to the Wrong Finish Line

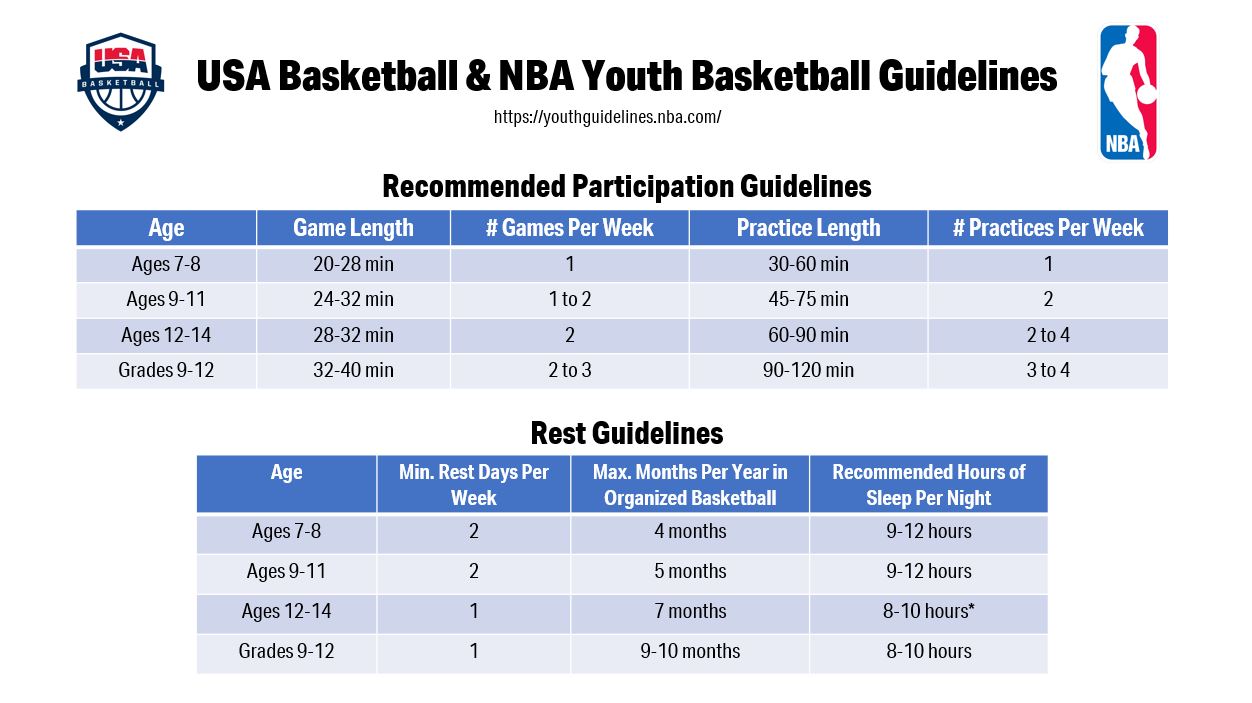

Recommended participation and rest guidelines for youth basketball athletes, from the NBA and USA Basketball.

Too often we try to accelerate steps 1 and 2—the introductory and foundational levels (12 years of age and younger)—and race to the advanced level with younger athletes. NBA legend Kobe Bryant agrees and stated the following in a Sports Illustrated article:

"Right now, I think we’re putting too much pressure on these kids too early, and they’re not learning proper technique of how to shoot the ball, or proper technique of spacing. It winds up eating away at their confidence. As teachers, we need to have patience to teach things piece by piece by piece. Over time, they’ll develop as basketball players, but you can’t just rush it all at once."

The Takeaway

A well-designed curriculum for the development of general athleticism, health & well-being, psycho-social values, and basketball-specific skills has been carefully considered by leading experts in sports medicine, strength & conditioning, child development, coaching, and basketball. In addition, there are ample resources provided for the coach, parent, and sport administrator to successfully implement a long-term basketball development program within a school, club or community. It’s time to adopt best practices at the youth level that will enhance the performance and participation abilities of everyone who enjoys the great game of basketball!

Resources

Join hundreds of thousands of coaches and athletes using Volt's intelligent training system. For more information, click here.

Learn more about Dr. Eisenmann | @Joe_Eisenmann