The Science of the NFL Combine: What High School Coaches Should Know

/"How much do ya bench?"

"What's your 40?"

Ah, we love to measure up and test our physical abilities. I hear these questions all the time in the high school weight room, albeit mainly from testosterone-laced adolescent male football players—some who dream of playing in the NFL. And if they are to achieve that long-term goal, they will more than likely pass through Indianapolis in late February at some point.

Every year during the last week of February (Feb 27th to March 5th, 2018) about 300 or so of the best college football players are invited to the NFL Scouting Combine in Indianapolis to showcase their abilities in front of NFL executives, coaches, scouts, and doctors. It is essentially a job interview consisting of a battery of physical, medical, and psychological tests in advance of the NFL Draft.

Historically, NFL teams would schedule individual visits to college campuses to test prospects. “The Combine,” as it is widely known, began in 1982 when the Dallas Cowboys president and GM Tex Schramm proposed a centralized scouting camp bringing all prospects to one location instead of the individual visits. Since that time, the Combine has grown in popularity to become a major sporting event attracting widespread media attention around not only the event itself, but also the preparation for it at various sports performance centers such as EXOS, IMG Academy, and more.

The NFL Combine Tests + Published Research: What We Know

What does the Combine test and why are those tests important? This intensive job interview consists of the following tests and drills over a four-day period for each position group:

Anthropometry/body measurements

40-yard dash (including times at 10 and 20 yards)

20-yard shuttle (also known as pro-agility or 5-10-5 shuttle)

3-cone drill (also known as L-drill)

Bench press (max repetitions at 225 lb)

Vertical jump

Broad jump

Position-specific drills

Medical and injury evaluation (may include MRI)

Interviews

Wonderlic aptitude test

The data from the physical tests are freely available online and has resulted in about 50 peer-reviewed scientific publications. Here is a summary of some of the key findings from selected papers (title, journal and publication year):

"Positional physical characteristics of players drafted into the NFL." Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2011

Generally, lineman performed worse in sprinting, jumps, and change-of-direction and better in the bench press, while wide receivers and defensive backs were the best performers in measures of speed, agility, and jumping. In general, offensive and defensive positions that commonly compete directly against one another display similar physical characteristics. These results can be used to establish position-specific profiles.

"The NFL Combine: performance differences between drafted and non-drafted players entering the 2004 and 2005 drafts." Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2008

In one of the first papers examining the physical tests, differences were examined between drafted and non-drafted skill players (wide receivers, defensive backs, and running backs), big skill players (fullbacks, linebackers, tight ends, and defensive ends), and linemen (offensive linemen and defensive tackles). Compared to non-drafted players, drafted skill players performed better in the 40-yard dash, vertical jump, pro-agility shuttle, and 3-cone drill. Big skill players performed better in the 40-yard dash and 3-cone drill. Drafted linemen performed better than non-drafted lineman in the 40-yard dash, bench press, and 3-cone drill.

"The NFL Combine 40-Yard Dash: How important is maximum velocity?" Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2017

As seen from the last paper and a widely held belief, speed is a vital component to success in football. This study analyzed the sprint velocity profiles during the 40-yard dash with split intervals at 10 and 20 yards. Think of putting a speedometer on the athlete from start to finish. Results indicated that maximum velocity (meters per second, which can be converted to mph) was strongly correlated with sprint performance at each segment (10, 20 and 40 yard times); however, the correlation at 10 yards was weaker than at 20 or 40 yards but still moderately strong, suggesting the independent role of acceleration from 0-10 yards as well.

The athletes were also split into fast and slow groups and it was determined that the acceleration pattern throughout the run—how the athletes reached maximum velocity (or sprint velocity profile) was similar between the groups. Overall, the results suggest including more maximum velocity training for athletes preparing for the NFL Combine. To get fast, you need to practice sprinting fast!

"The NFL combine: does it predict performance in the NFL?" Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2008

This study found no consistent relationship between performance tests and professional football performance expressed as draft order, 3 years each of salary received and games played, and position-specific metrics (passing yards, sacks, tackles, etc.), except for the sprint tests for running backs. Thus, the authors questioned the overall usefulness of the Combine and offered the recommendation of “overhauling the combine process with the goal of creating a more valid system for predicting player success.”

"Epidemiology of injuries identified at the NFL Scouting Combine and their impact on performance in the NFL." Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 2017

If NFL owners are going to invest millions in a player, they want to be assured that they can play. Again, this is a job interview. Owners do not want lost productivity or players on workman’s compensation. Football is a collision sport, and thus injuries are part of the game. Among athletes at the NFL Combine, the most common sites of injury were the ankle (53% of athletes), shoulder (52%), knee (51%), spine (36%), and hand (33%). Overall, performance in the NFL worsened with injury history.

The "Underwear Olympics"

In the past few years, the NFL Combine has received scrutiny and is often jokingly referred to as the “Underwear Olympics”—guys running around in tight spandex shorts. Two years ago, I attended the first NFL symposia on technology and sports science to address potential changes to the NFL Combine. However, change is hard and it appears that the testing protocol remains the same this year.

Of course, what is left out is that there are also subjective assessments occurring simultaneously during the performance tests and the on-field position-specific drills—how the athlete moves. Let’s just call it “the coach’s eye.” In addition, several NFL personnel highly value the interviews which can shed light on personality, aptitude, and “cultural fit” within an organization. There is also that “gut feeling.”

Combine Considerations for High School Coaches

There are several excellent points and considerations about the utility and predictability of the testing and screening process of the NFL Combine that can be gleaned to educate the high school coach when incorporating testing and assessment of their athletes.

Many high school coaches conduct testing in their programs and perhaps even host combine testing days. I want to use this section as a means of educating coaches on the why’s of testing. But first, let’s back up. What really is the purpose of testing anyway?

For several years, I taught a course in Measurement and Evaluation for Kinesiology students and the first lesson was always on the definitions and the nature and purposes of testing and evaluation. Overall, the purposes of measurement, testing, and evaluation include:

Diagnosis

Prediction

Placement

Motivation

Achievement

Program evaluation

The NFL Combine is largely a matter of diagnosis and prediction. Athletes are being diagnosed physically, mentally, and medically and NFL stakeholders are trying to predict their ability to play in the NFL. For some athletes, performance at the Combine may also influence placement in draft order and round. As a high school coach, you are also doing the same, but I would argue that the latter three purposes of measurement, testing, and evaluation—motivation, achievement, and program evaluation—may be more important for the high school coach and athlete.

Testing for Placement

First, let’s reconsider placement. A baseline test and evaluation can provide information on potential positional group for an athlete and also allow you to group athletes into training groups according to physical attributes and abilities. An important element of placement is evaluation. Evaluation involves decision-making and statements about the quality of the characteristic being measured (e.g., good, average, poor). Evaluation can be differentiated in a couple of ways including norm-referenced or criterion-referenced. Norm-referenced evaluations are based on comparisons to a well-defined group (e.g., athletes of same age and gender), while criterion-referenced evaluations are based not on how you compare to a group of peers but whether the athlete has achieved sufficient ability to meet a specific criterion or standard (e.g., a minimum criterion of some sort).

In other words, do you compare an athlete’s score to the group average at your school? Or do you compare them to national reference values? Is the value that you use for comparison linked to a standard like All-State or reduced risk of injury?

Testing as Motivation

Next, and one that I believe is quite important: using testing for motivation. Some people state that academic grades are bad because people don’t “try to learn,” they just work for the grade. However, consider the effect if the teacher said that there would be no assignments, no tests, no attendance policy, no homework, etc. To make the students feel good about the class, content, and learning, there would be no pressure to achieve. How motivated would students be? I don’t think that they would be very motivated. You could also use the example of the score in a game. Would thousands of people attend a college football game if there was no measurement (i.e., score) kept? Testing can help motivate athletes in a similar manner. The key thing is that athletes need to be motivated to achieve Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Timely (SMART) goals. Are you using goal setting that is SMART?

Once a baseline measure is obtained and goals are set, subsequent testing can help with the achievement of these goals and program standards. Finally, testing is a good way to evaluate your strength and conditioning program and your overall program. Is the program effective? Is there a relationship between accountability and strength gains? And remember, program evaluation needs to go beyond wins and losses.

Is Combine Testing Appropriate for Young Athletes?

With that said, a final note for consideration relates to going beyond the typical strength and conditioning numbers for bench press, squat, 40-yard dash and vertical jump when developing young athletes. I have spoken to many high school football coaches specifically about this matter. Remember: we do not put a bench press on the 50-yard line on Friday night and see who benches the most.

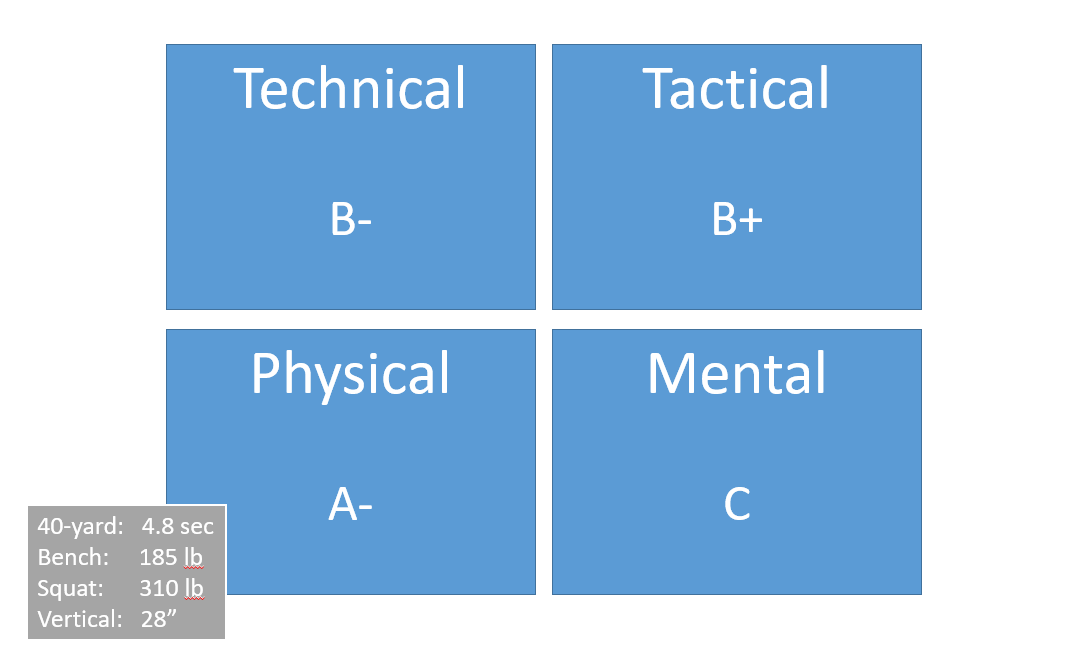

Now, don’t get me wrong—the physical attributes of strength, power, speed, and agility that are the focus of off-season conditioning are important to athletic performance. However, we all know the athlete who has incredible combine numbers but cannot catch or block, or has a poor sports IQ or is a “head case” with poor mental skills. Thus, the development of the young athlete needs to take on a holistic approach, and should also be considered when testing and training. Think of establishing an athlete report card or dashboard that addresses the technical, tactical, physical and mental aspects of the athlete. Plus, also consider injury history and prevention of common injuries in your sport by working alongside the certified athletic trainer and/or team physician. Similar to the NFL in their overall evaluation of prospects, it is important to recognize all the different facets of performance when assessing a player and when designing programs to improve performance in individual athletes.

A sample "Report Card" for an athlete that includes Combine testing data in a more holistic assessment.

The Takeaway

Need help with testing and evaluating physical tests in your athletes? Check out this Performance Assessment Package from our partners at the National Strength and Conditioning Association, which includes the Four Steps to Success to help monitor the development of athletes, measure the effectiveness of the training programs, and motivate athletes to achieve their training potential.

And let’s end with something to think about: what gets measured gets managed—but are you measuring what really matters?

Join hundreds of thousands of coaches and athletes using Volt's intelligent training system. For more information, click here.

Learn more about Dr. Eisenmann | @Joe_Eisenmann