Hitting the Wall, Part 1: What Is It and What Does It Do?

/I ran a marathon once. Emphasis on “once.” Double emphasis on “never again.”

It was the Portland Marathon six or seven years ago, and it was raining like the end of the world. My shoes were filled with water by mile five, marking my cadence with a rhythmic squish-squash for the remaining 21.2. But it wasn’t the water that brought me to tears at the 18-mile marker—it was the Wall.

While some call it “bonking,” I prefer the metaphor of “hitting the wall”—because it really feels like you've run into some sort of physical and psychological barrier that suddenly knocks you down. Most distance athletes are familiar the Wall, and what it feels like when you hit it. It’s more than just tired muscles and creaky joints. It’s a drastic, unpleasant change in your body’s ability to exercise at a given pace for a long period of time.

I’ve heard marathoners describe the Wall as an elephant that suddenly jumps onto your shoulders, or feet that turn into scuba fins, or like trying to tread water while simultaneously stuck in quicksand. When I hit the Wall in my soggy marathon attempt, it felt like suddenly the road was one of those walking sidewalks in the airport, except that it was moving backwards while my body was frantically (pitifully) trying to move me forwards. If I had been a Game of Thrones fan back then, I would have immediately equated my physiological wall with the 8-millenia-old Wall of solid ice that guards the citizens of Westeros against the White Walkers of the North.

So, what exactly is the Wall, and why do we hit it?

What is "the Wall"?

@@Put simply, you hit “the wall” when your body runs out of carbohydrate fuel—a state known as hypoglycemia.@@

The body’s primary fuel sources are carbohydrates—stored in the blood as glucose, and in your liver and muscles as glycogen—and fats. The relationship between carbs and fat as fuel sources in the body is a complex one: carbs provide the energy the body needs for high-intensity (anaerobic) and short-duration work, while fats (because they can be metabolized in the presence of oxygen) are the primary energy source for longer bouts of lower-intensity (aerobic) exercise. But while a marathon would definitely qualify as an “aerobic” sport, fat is not the limiting factor in aerobic performance. Why is this?

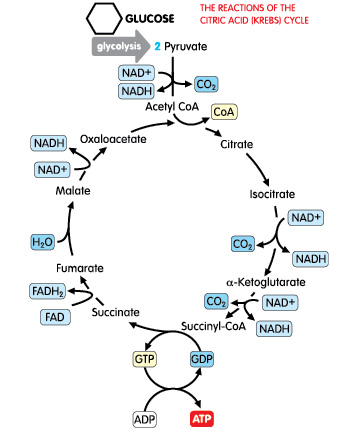

The Krebs Cycle produces lots of energy for exercise, but requires glucose (carbs) to keep running.

Because, to quote a biochemical adage, “Fat burns in a carbohydrate oven.” When carbohydrates are broken down for energy during glycolysis, glucose molecules are converted to pyruvate, which is then converted to acetyl coenzyme A. Acetyl-CoA is the primary substrate for another energy-yielding process known as the Krebs Cycle (or Citric Acid Cycle), which takes place in the mitochondria of cells and serves as the body’s combustion engine. The Krebs Cycle can produce a TON of energy from both carbs AND fats, but it can become inhibited due to lack of carbohydrates in the body. The less glucose available for breakdown, the less pyruvate and Acetyl-CoA are produced as a result of glycolysis—which then limits the functional rate of the Krebs Cycle. Fats are converted into energy via the Krebs Cycle, after undergoing lipolysis to convert them into Acetyl-CoA—but if the Krebs Cycle is inhibited from lack of carbs, the Acetyl-CoA from fat has nowhere to go. So, when you don’t eat enough carbohydrates, the Krebs Cycle effectively stalls—and your body cannot burn fat. The quantity of energy being made from fat is dependent upon the rate of carbohydrate metabolism: “Fat burns in a carbohydrate oven.”

All this biochem stuff is important for distance athletes to understand because it illustrates the partnership between carbs and fats in the body’s energy systems. When your body runs out of carbohydrates to burn—which can happen during aerobic exercise > 90 minutes in duration—you can’t simply “switch” to burning fat instead, since fat can’t be utilized without carbohydrates. Carbs are the limiting energy factor, even in endurance activity.

What Does the Wall Do?

While your body has plenty of carbohydrate available at rest, it’s a different story in a 5-hour bike race, Ironman triathlon, cross-country skiing event, or marathon. If you don’t continually add more fuel, it can spell disaster for your body—and your mind. It’s not just your muscles that need glucose: your brain needs glucose, too. So when you run out of glucose and hit the wall, you don’t just feel sluggish and weak in your body—you can also experience cognitive symptoms, too. Like depression, disorientation, dizziness, anxiety, hostility, and light-headedness.

Just ask my mom about when she met me at mile 22 of my ill-fated marathon. By this point, my shoes were like size-7 boats, swollen with water and weighing what felt like 15 pounds apiece. My shoulders slumped forward, my knees were sending bolts of pain up my femurs, and my entire body felt as if I’d been trampled by a thousand Dothraki warriors on horseback.

During my marathon, my body felt like Khal Drogo himself had come back from the dead (spoiler alert) to make my life miserable.

The 22-mile marker came at a particularly scenic part of the race, in a beautiful neighborhood on a hill overlooking all of downtown Portland. It was so pretty, in fact, that two other runners had chosen to get married there, two-thirds of the way through the race. The bride wore a white tennis dress with her running shoes, the groom a Dri-FIT t-shirt with a tuxedo printed on the front. They were standing in the pouring rain with their bridal party (runners) and officiant (also a runner), just so in LOVE and so HAPPY to be running a MARATHON together and get to run MARATHONS together for the rest of their shiny, happy lives…and I have never hated any two human beings more in my life.

Depression—and hostility—had set in. When I saw my mom in the cheering crowd minutes later, I burst into tears (though you couldn’t see them, since my face was already streaming with rain water under the brim of my visor).

Looking back, I can blame my complete emotional collapse on CNS fatigue. The Central Nervous System (your brain and spinal cord), just like your muscles, gets tired from prolonged exercise. During long periods of sustained activity, the brain’s production of serotonin steadily increases, while its production of dopamine production decreases. These two neurotransmitters work opposite to one another: higher serotonin levels can increase your perception of effort and muscular fatigue, while lower dopamine levels can decrease athletic performance and motivation. So when your nervous system becomes fatigued during long bouts of exercise, your brain tells you that you’re more exhausted than you really are, and signals you to feel unmotivated and unhappy. It’s a neurological one-two punch, right to the emotions—making you feel all the feels that you don’t want to feel at mile 22.

How Can I Avoid Hitting the Wall?

Fear not: this story has a happy(ish) ending! Tune in to Part 2 next week to learn more about the Wall, and how you can train to soften its blow (and even avoid it altogether). After all, marathon season—like winter—is coming...

Join over 100,000 coaches and athletes using Volt's intelligent training app. For more information, click here.

Learn more about Christye and read her other posts | @CoachChristye