Pieces of the Puzzle: How to Improve Your Vert, Part 2

/Following up on Part 1, we understand that POWER is the primary ingredient in an impressive vertical, and that we can improve our power by increasing the amount of force we can produce (specifically in the squat). Power is two-sided: while we need to produce large amounts of force, we also need to produce that force quickly. The speed at which we produce that force is termed the rate of force development, or RFD for short. RFD can be even more simply defined as athlete’s explosive ability. The faster you can recruit maximal strength, the more explosive you become. We know that improving the strength in the squat is step one, but we can’t neglect the second piece of the puzzle. Having a huge squat doesn’t correlate to a huge vert. Applying that force explosively is the next piece of the puzzle, and a fun and challenging one at that.

Three primary methods exist within Volt programming that shine as effective tools for increasing vertical jump ability. The goal behind all three is to improve the rate of force development behind triple extension ability. The faster you can recruit maximal strength in explosive extension of the hips, knees, and ankles, the higher your vertical jump will inevitably become.

Olympic Weightlifting Movements

Olympic weightlifting is comprised of the Snatch and the Clean + Jerk movements. While Olympic lifting exists as its own complete sport, using these movements and their variations are effective tools for producing powerful athletes. The very nature of these movements require athletes to recruit force dynamically and with powerful hip extension, mimicking extension mechanics similar to jumping. Using partial movement variations like the Hang Clean and Hang Snatch allow for the hip extensors to receive an eccentric stress similar in mechanics to the pre-loading phase of a maximal-effort jump. Dumbbell variations offer reduced intensity and are an easy way to progress the learning process of actively loading a hip hinge followed by an explosive extension of the hips, knees, and ankles. The main goal in the Volt Program is to challenge athletes to recruit the hip extensors explosively under load, stressing both force production and speed of movement simultaneously. With Olympic weightlifting, there is a limit to effectiveness. At a point, an athlete will no longer be progressing in power production, but rather progressing in the skill of the lift.

Because Olympic weightlifting carries such a high technical demand, athletes can improve by becoming more talented lifters rather than more explosive athletes. For this reason, we don’t rely on Olympic weightlifting as the only source of RFD improvement. Maintaining variety in how you produce high power is important. What works extremely well for one athlete, may not work as well for another.

Plyometrics

When it comes to jump training, you can't get too far before you start talking about plyometrics. In a nutshell, plyometric training refers to training that emphasizes the elastic components of muscle and tendon to facilitate explosive movements using jumping, bounding, ballistic, and reactive movements. Plyometrics can be unloaded or loaded, stationary or moving, unilateral or bilateral, and can use any portion of the body. Broad jumps, tuck jumps, box jumps and med-ball throws all fall under this category. The main mechanism behind plyometrics is the stretch shortening cycle (or SSC) and it is the key component in any dynamic movement. When an athlete performs a vertical jump, the initial movement is to swing the arms back and hinge at the hips to “load” the jump. This pre-stretch stores kinetic energy in the muscle and tendon that can be utilized in the subsequent explosive jumping movement. Plyometric training allows athletes to develop a greater ability to harness more energy in the pre-stretch, and to utilize more of that energy into the jumping effort.

Plyometrics bridge the gap between raw strength and power, but don't mistake them for just jumping continuously. The goal of plyometrics is to focus on high-quality explosive muscle action and maximize the energy potential of all the movement pieces involved. A progressive plyometric program should transition from sub-maximal efforts with minimal complexity, to higher demands on distance, effort, and height. Spending time progressing from squat jumps, to box jumps, to a dumbbell box jump allow for an athlete to focus on the quality of each jump AND appropriate landing position.

Plyometrics can be intense and stressful if not programmed correctly, or if an athlete has not progressed effectively through a sound developmental process. Increasing the number of jumps, the height of the jump and subsequent landing, or the load of the movement can all place muscles and tendon under exaggerated intensities. This is a big reason why a developmental strength program is a huge benefit for athletes to get the most out of plyometric training.

Post-Activation Potentiation Methods

Pairing both heavy resistance training and plyometrics has been shown to be an effective method for developing power. Commonly known as Complex Training, the training method challenges a motor pattern against heavy resistance (strength focus) and then pairs it with a plyometric movement of the same basic pattern (plyometric focus). As I've written before, the secret sauce of complex training lies in the phenomenon known as Post-Activation Potentiation, or PAP for short. After a muscle fiber contracts under heavy load, the inner workings of the muscle fiber are left in what’s called a potentiated state. All this means is that the following muscle contractions used in the plyometric movement are stronger and faster due to being in a previously excited state and have increased nervous activity. For a real world example, the strength you need to move a heavy deadlift recruits more muscle fibers than you would use in a high box jump. Performing a set of deadlifts and then performing a set of high box jump allows more muscle fibers to be recruited into the jumping movement, thus increasing the force utilized in the plyometric movement. Complex Training places emphasis on both the strength AND speed of recruitment, thus allowing athletes to train at higher levels of power output.

Justin D. Smith, Co-Director of Athletic Performance at the University of Vermont (UVM) and Volt Advisor, implements unique forms of post-activation potentiation training to maximize his athletes’ power potential in the peaking phases of his training calendar.

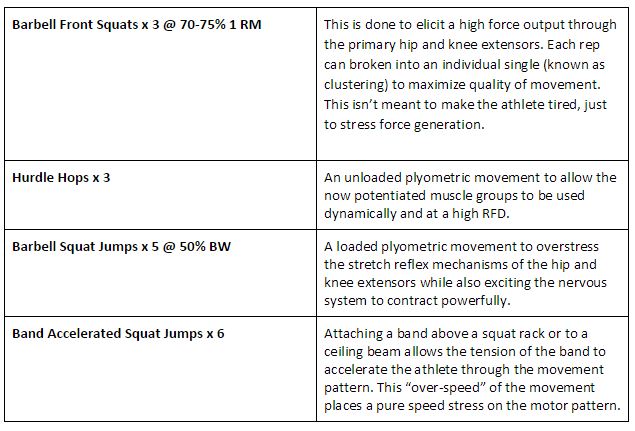

Using a similar method known as Contrast Training (based on Coach Cal Dietz’s “French Contrast” in his book Triphasic Training), Coach Smith runs his athletes through four different movements, each with a specific training purpose to elicit a high stress on the nervous system to facilitate faster and more explosive movement using the effects of PAP.

The Contrast Method calls for a loaded strength movement, an unloaded plyometric movement, a loaded plyometric movement, and an accelerated plyometric movement.

Here is an example of how it looks in application:

All movements play into driving a high neural stimulus to maximize his athletes’ ability to move explosively. The purpose is to stress a high number of motor units, recruit them explosively, re-apply stress with higher eccentric and plyometric demand, and finally to apply a pure speed stress across the entire movement pattern.

The results have helped push some athletes to reach National and Elite levels, and for both the US and International Olympic programs.

Keep in mind, this is highly specific training for highly specific athletes. The level of foundation and development needed is incredibly high. Beginner and intermediate athletes may not benefit as much from such a highly specific method of PAP training. Not to mention, this style of training is reserved for peaking phases, when athletes need to be developing as much power as possible. There is always a proper time and place for certain training goals. Coach Smith progresses his athletes for years at a time before they have a foundational strength and skill level necessary for this style of training to be as effective as possible. This further highlights why having a structured training plan for your season and sport goals is a huge benefit towards maximizing your performance.

When it comes to improving the vertical jump there are two primary training goals you should make a priority: 1) Improve force output, and 2) Improve the speed at which that force generated. How you do that can be completely variable based on your size, your genetics, training history, and current training goals.

Join over 100,000 coaches and athletes using Volt's intelligent training app. For more information, click here.