All about The Psoas

/Summary of Article:

The psoas—your body’s “filet mignon”—is the strongest hip flexor and plays a critical role in posture, athletic movement, and injury prevention.

Tight or overstretched, a dysfunctional psoas can cause pelvic imbalances like anterior tilt (“duck butt”) or posterior tilt (“flat butt”), limiting mobility and increasing injury risk.

Understanding your posture and movement patterns is key to identifying whether your psoas needs stretching or strengthening.

Use simple self-assessments like the Thomas Test, the Two-Hand Rule, or a supine leg raise to evaluate psoas health. Tools like Volt’s readiness survey help athletes track recovery and avoid overtraining-related issues.

Imbalances between the psoas, glutes, and abdominals can lead to compensations and chronic pain.

ou can even have a psoas that is both tight and overstretched depending on how your pelvis is positioned and which muscles are overactive.

The takeaway: listen to your body and address what your unique anatomy is telling you.

For some, this means stretching the psoas. For others, it’s about strengthening it—or targeting surrounding muscles like glutes or abs. The key to a high-performing “filet mignon” is balance.

Ah, the iliopsoas; often referred to as the filet mignon of muscles. If you’ve ever ordered filet mignon at a steakhouse, you may be surprised to learn that it comes from a cow’s hip flexor. And while I suppose this information might come in handy if you were trapped on a desert island and forced to resort to cannibalism and had to know which human muscle would be the most tender, tasty choice for your survival needs (that got pretty dark...), it's also just a good muscle to know.

Your psoas is essential to your ability to move well and important to understand when training your body for better athletic performance. Out of all the muscles that work to flex the hip, your psoas is the strongest.

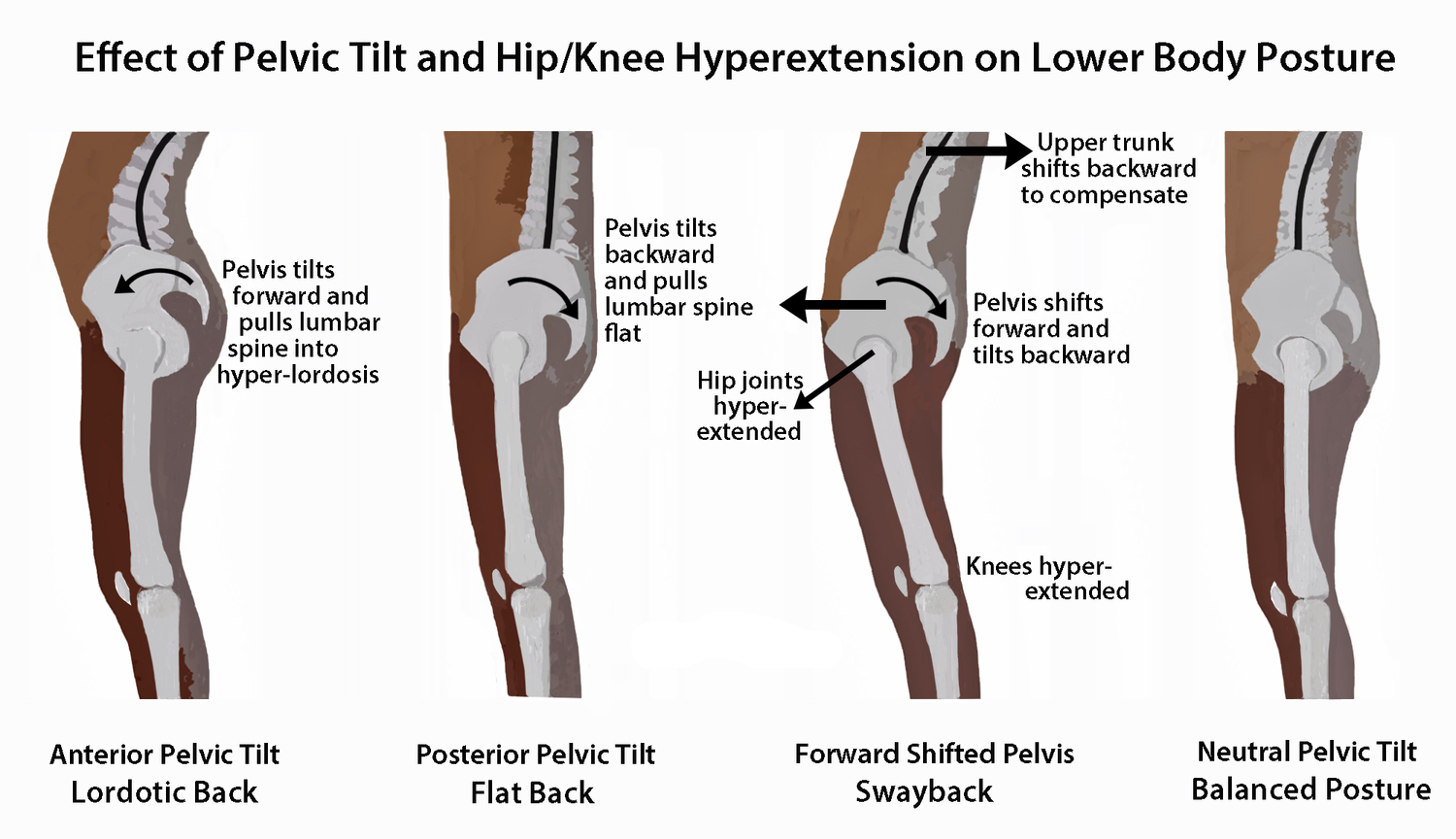

Anterior tilt ("duck butt"), posterior tilt ("flat butt"), and forward pelvic shift ("swayback") are affected by the health of the psoas, and can put your body into compromising positions.

The dilemma for many athletes? Knowing the status of their psoas. Familiarizing yourself with this muscle, its intended functions and the way it functions within your own body will help you know which type of maintenance—strengthening or stretching—your psoas needs for you to move better.

Pro Tip: The Volt Training App has a readiness survey for athletes to complete before each workout, helping you tune in and identify trends for when you are most energized and to know when you need a rest to avoid overuse injuries.

Where is it? What is it? What does it do?

The psoas major and iliacus join forces to effectively flex your hip joint.

The iliopsoas is technically a group of two muscles comprised of the psoas major and iliacus. These muscles originate in different places (the psoas major at the lumbar vertebrae and the iliacus at the pelvis), but unite with each other to cross the hip joint and attach at the femur. It’s a tale of two muscles from different neighborhoods, joining forces to work toward one common goal (I’d totally see that movie!).

Because they are virtually indistinguishable at their distal end, functioning as one muscle to flex and laterally rotate (supinate) the thigh, they are usually referred to as the “iliopsoas” (although I’m going to use just “psoas” in this article, because I’m talking mainly about the spine-to-femur functionality of the iliopsoas). The psoas is active when you walk and run, flexing the hip to move your leg forward and then lengthening to allow the opposing movement of hip extension, accomplished (primarily) by the gluteus maximus. Your gluteus maximus and your iliacus work on opposite sides of the hip as antagonist muscles, meaning they have an inverse relationship with one another—when one contracts, the other must relax to allow movement in the opposite direction. So when your psoas is too tight, it pulls your gluteus maximus into an overstretched state, and vice versa.

A shortened psoas (from sitting too much) can lead to a hyperlordotic lumbar spine, but not every psoas is short and tight.

Most of us sit a lot during the day, compressing the front of the hip and thus the psoas, and because of this, I see blanket prescriptions for hip flexor stretching all over the Internet. But if you, or an athlete you know, has pain originating at the front of the hip joint, stretching the psoas may actually do more harm than good! Knowing whether your psoas is short/tight and needs stretching, or weak/overstretched and needs strengthening is crucial for preventing injury and improving performance.

Is My Spine Neutral?

A great place to start in assessing the state of your hip flexors is examining your standing posture—specifically, the position of your spine as it attaches to your pelvis.

Your spine has two natural curves: slight flexion in your thoracic spine (kyphosis), and slight extension in your lumbar spine (lordosis). If either of these curves is exaggerated, it compromises your spine’s ability to move and stabilize your trunk. When the musculature of your hips is out of balance, your spine will deviate from its neutral curves, placing you at risk of pain and injury. To tell if your psoas is tight or overstretched, stand sideways by a mirror (or even better, have a friend take a photo of you from the side). Note the position of your pelvis—if you were to draw a line along your pelvis from back to front, that line should be pretty straight. If the line tilts downward, your pelvis is anteriorly tilted (toward the front of your body) and your psoas may be short and tight. If the line runs upward, your pelvis is posteriorly tilted (toward the back of your body) and your psoas may be overstretched and weak.

Anterior pelvic tilt may indicate a tight, short psoas. Posterior pelvic tilt may indicate an overstretched psoas. What does your pelvis indicate?

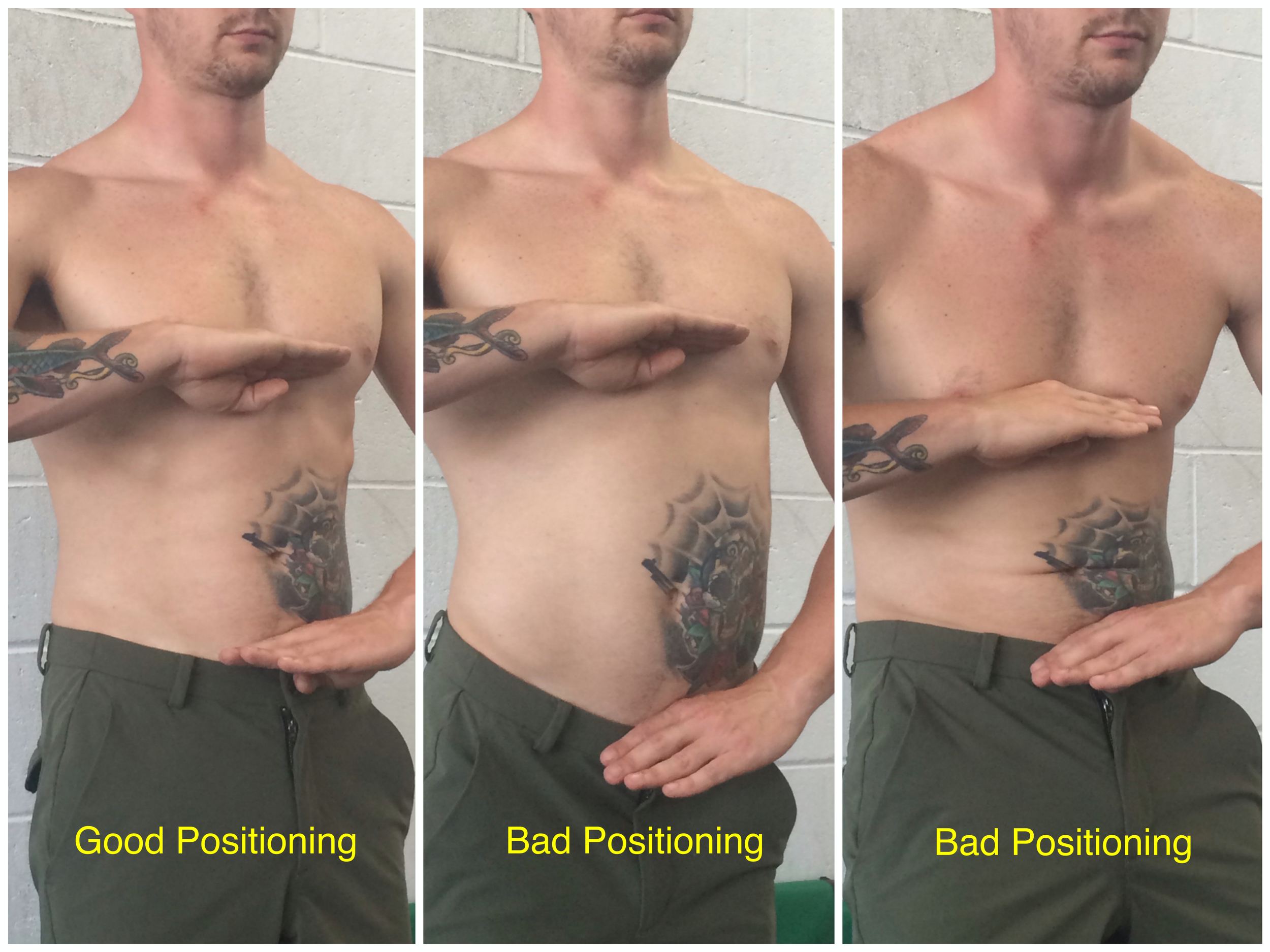

This nice, tattooed man demonstrates the Two-Hand Rule of pelvic neutrality.

Another great postural diagnostic tip is the "Two-Hand Rule," gleaned from Kelly Starrett’s book, Becoming a Supple Leopard, is to place one thumb on your sternum (keeping your hand splayed, palm facing down) and the other on your pubic bone. Angle both hands so they continue along the same horizontal plane as your ribcage and pelvis. If your hands tilt either in towards each other, or out away from each other, you are deviating from a neutral spine position.

How Can I Tell if My Psoas is Tight?

Hip flexor tightness can manifest itself in all sorts of aches and pains. A shortened psoas tips your pelvis forward, compressing the hip socket and preventing your leg from moving independently of your trunk. Your body, prevented from rotating at the ball-and-socket hip joint, then tries to compensate by forcing rotation at the low back or knees. And this, as you can guess, can lead to some yucky stuff.

If your psoas is tight, you will test positive in a PT diagnostic tool called the Thomas Test. To perform this test, find a table or flat surface high enough for you to lie on, face-up, knees hanging off the edge, without your feet touching the floor. Keeping your low back flat against the table, slowly bring one knee into your chest. If your opposite thigh comes up off the table, you test positive for tight hip flexors.

The video above is the best I’ve found for illustrating the biomechanics of the Thomas Test, and the different possible outcomes.

For example, you have another muscle that helps to flex the hip: the rectus femoris (your major quadriceps muscle). And it is possible for your rectus femoris to be tight, while your psoas is not. As this short video explains, when you bring one knee into your chest, and the knee of the opposite leg extends WITHOUT your thigh coming up off the table, your rectus femoris is tight but your psoas is not.

This test is a great tool for determining whether your psoas is shortened—but what about athletes whose hip flexors are too long?

How Can I Tell if My Psoas is Overstretched?

When muscles are chronically overstretched, they can’t produce as much force. The reason behind this goes down to the cellular level of the muscle fiber, and how it produces contraction (a shortening of the muscle). Put simply, muscle contracts when teeny proteins in the muscle fiber overlap and slide toward one another, shortening the muscle. When a muscle is stretched beyond its normal resting length, there is less overlap, and thus less contractile force. To illustrate this, flex your elbow to 90 degrees and contract your bicep. Now try to contract your bicep with your arm straight and elbow fully extended. It’s much harder to produce contraction when the muscle is fully lengthened—and it’s even harder when the muscle is lengthened beyond its normal range.

If your psoas is overstretched, hip flexion exercises will be difficult for you because those muscles can’t produce as much force. You also might experience pain in the front of your hip capsule, due to laxity in the joint caused by a lack of tensile strength.

Try performing a simple, supine double-leg raise: lie on the floor on your back, with your lumbar spine in a neutral position and your legs at 90 degrees. Slowly lower both legs toward the floor, maintaining the neutral position of your low back. Without releasing the contraction, slowly raise both legs back to the starting position. If you cannot perform 10 controlled reps, either due to muscle exhaustion or inability to maintain spinal neutrality, your psoas might be weak and potentially overstretched.

Can My Psoas Be Tight AND Overstretched?

Here’s where sh*t gets real. Let’s say you sit all day in a bad position, then head to the gym to work your glute max and abdominals (gotta get that six-pack). Now your GM muscles are really tight, pulling your pelvis into a posterior tilt and stretching the psoas. This can create a lot of instability at the front of the hip capsule. And what does your psoas do when it senses the joint is too unstable? It tightens up to protect it! So you stretch your psoas, releasing the tension and restoring its length...which leaves your tight GM and rectus abdominis muscles more leeway to continue pulling. They keep pulling the pelvis backward, and your psoas gets even more stressed—and stretched—out.

A posterior pelvic tilt can cause the lumbar spine to lose its natural, healthy curve and cause pain at the front of the hip joint. With time, restricted glute muscles contribute to psoas lengthening, which can cause your psoas to react defensively and tighten itself to maintain hip stability.

The point is that the relationship between your glutes, your abdominals, and your hip flexors is complicated. If your pelvis has a tendency toward an anterior tilt, you might be operating with weak abdominals, and no amount of psoas stretching will fix that. But if you tend to have a posterior pelvic tilt, a tight GM, and not an overstretched psoas, may be the real culprit. There is no one-size-fits-all prescription for taking care of your hip flexors. The way we sit, and the muscular imbalances we all develop over time, influence the state of our psoas, and only you (or your bodywork practitioner) can know what’s going on with yours. Practicing awareness of your hip flexors, in relationship to their surrounding musculature, will help you find out if your psoas needs stretching, strengthening, or something else entirely.

The Takeaway: the body is all about balance - left to right, and front to back.

When looking at the psoas, we’ve got to look at the muscles that help maintain balance during hip flexion. For some, this will mean stretching a tight and painful psoas. For others, it might mean foam-rolling a short, tightened glute max to relieve an overstretched psoas. And others might need to strengthen their abdominals to release a tight psoas and fix their “duck butt.” Listen to what your psoas is telling you! Pay attention to your pelvis! Your body will tell you what your psoas ultimately needs—and then it’s up to you to keep your “filet mignon” strong, supple, and ready for action.