Why the Front Squat is Your Best Friend: Part 2

/The front squat is so nice, I had to blog about it twice. To get up to speed, check out part one. Here are 3 more reasons to love and adore the all-important front squat.

1. It's The Squat That Can Help Fix Your Squat

Front squats can help both highlight mobility issues that restrict your athletic performance, and take your back squat to a whole new level. While the overhead squat is arguably the best movement assessment tool, front squats don’t require you to hold a bar/dowel overhead, and are therefore more manageable for most athletes. The front squat highlights technical flaws that can hamper ALL other squat movements, and thus functions as a useful diagnostic test to identify the areas of your squat mechanics that need corrective training.

If you’re missing much-needed ankle dorsiflexion, the front squat will let you know. Same goes for tight hamstrings and T-spine mobility. And if your front squats are ugly, chances are your back squats aren’t going to be the belle of the ball.

Luckily for you, improving your strength in the front squat will set a better foundation for your back squats. Think about it: the back squat requires strong quadriceps and a torso that can maintain a strong upright position—both of which are trained with the front squat. Since the bar rests in a forward position in the front squat, greater activation of the quads is required to maintain proper form—and the core muscles are forced to work harder to keep your torso upright (2, 4). Better front squatting leads to better back squatting leads to better athletes. Boom. But if I can’t persuade you, then maybe Dan Green can. When you see a guy front squat over 600 lbs with perfect spinal and hip position, you tend to listen to what he has to say. Here he is getting some reps in....with 573 lbs on the bar (cue shocked gasps).

2. Front Squats Are Safer

This is NOT to say that back squats are unsafe or injurious—let’s simply look at what the research shows about how front squats affect the body in comparison to back squats.

Studies comparing the kinematics between the two squatting styles show that front squats place less shearing force on the knee and spine, while maintaining the same level of muscular activation (3, 4). This is intriguing information because it shows that we can get a similar training response from squatting, while minimizing any risk to certain areas of common injury in athletes. The front squat can thus be used as an effective tool in retraining proper mechanics with less loading, to ease the relearning process.

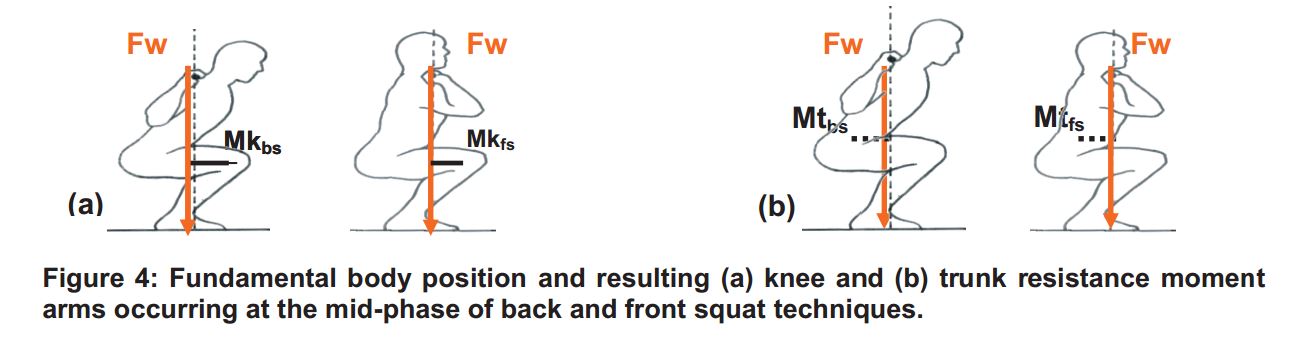

The following illustration from Diggin et al demonstrates how the position of the bar in the front squat keeps the bar closer to the athlete’s center of gravity, which reduces the moment arm between both the spine and knees. The back squat requires a natural forward tilt, which, while engaging more musculature, increase the amount of shear stress on the spine and knees.

From Diggin et al, 2011.

The front squat provides additional safety because, unlike the back squat, heavy attempts at front squats can be missed safely, and without the need for a spotter. An athlete can simply shift their hips backwards, and push or guide the bar down to the floor without any risk to themselves or others. The feeling of getting pinned down by a heavy back squat is a dreadful experience (trust me on this one), and with heavy attempts upwards of three spotters are needed to ensure an athlete’s safety in case he or she gets pinned down. Heavy front squats, on the other hand, will never reach the same loads as the back squat and therefore do not require a spotter, increasing the overall safety of everyone in the gym. This doesn't mean you should allow yourself to get into the habit of missing front squat attempts, but it reassuring to know there is much lower risk of injury associated with the front squat.

3. Front Squats Increase Athleticism

Something about rugby players tells me they squat.

Finally, the front squat is a beautiful blend of demands—on posture, flexibility, and muscular recruitment—that help train many pathways at once. This combination of demands pays dividends when you are training to increase many athletic traits. A study of Division 1 male volleyball players showed that the front squat was just as effective at improving vertical jump height as the back squat (6). The trunk stability required to remain upright during the front squat challenges your entire kinetic chain to produce force. It also challenges athletes to keep ideal body positions related to vertical takeoff, absorbtion of landing forces, and reactive power. Another study, this one of rugby players, found that athletes with higher 1RM squat numbers had better short sprint speed and ability to change direction—and it correlated to a higher 1RM hang clean (5).

The Takeaway

The front squat is a foundational tool athletes can use to practice a multitude of translatable athletic skills, thereby increasing their overall potential. Improving your front squat will translate to improved ability to accelerate, decelerate, power through contact events, and use explosive power from the bottom of the squat position. On the whole, the front squat is a valuable movement that ALL athletes can implement. Consistent practice will produce favorable adaptations, not only in mobility, but also in better overall body awareness. So if you find yourself making slight adjustments to compensate for mobility restrictions, keep squatting! Eventually you’ll develop enough flexibility in your hips, hamstrings, ankles, and wrists to load up heavy. Who knows—maybe you’ll even get hops like Bill Gates.

Join over 100,000 coaches and athletes using Volt's intelligent training app. For more information, click here.

References

1.) Bird, S. P., & Casey, S. (2012). Exploring the Front Squat. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 34(2), 27-33.

2.) Braidot, A. A., Brusa, M. H., Lestussi, F. E., & Parera, G. P. (2007, November). Biomechanics of front and back squat exercises. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 90, No. 1, p. 012009). IOP Publishing.

3.) Diggin, D., O’Regan, C., Whelan, N., Daly, S., McLoughlin, V., McNamara, L., & Reilly, A. (2011, July). A biomechanical analysis of front versus back squat: injury implications. In ISBS-Conference Proceedings Archive (Vol. 1, No. 1).

4.) Gullett, J. C., Tillman, M. D., Gutierrez, G. M., & Chow, J. W. (2009). A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(1), 284-292.

5.) Hori, N., Newton, R. U., Andrews, W. A., Kawamori, N., McGuigan, M. R., & Nosaka, K. (2008). Does performance of hang power clean differentiate performance of jumping, sprinting, and changing of direction?. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 22(2), 412-418.

6.) Peeni, M. H. (2007). The Effects of the Front Squat and Back Squat on Vertical Jump and Lower Body Power Index of Division 1 Male Volleyball Players (Doctoral dissertation, Brigham Young University).