The Complicated Relationship Between Baseball and the Bench Press

/Last year I wrote a piece on the bench press that sought to mitigate some of the animosity this movement receives from sport coaches. While it helped calm the worries of coaches who felt bench pressing was strictly an option for meat-heads and bodybuilders, there still exist some negative feelings about the lift from certain sport coaches.

One sport that seems to hate the bench press in particular is baseball. And the hatred is somewhat justified, especially when it comes to athletes with certain soft tissue restrictions or athletes who will simply bench for the sake of benching. There are some very good articles that have been written that explain why overdoing the bench press can be a net negative for the baseball athlete. Unfortunately, some coaches read these articles and get the impression that any manner of bench pressing is either a waste of time or will have an entirely negative effect on their athletes. As I’ve said before, bench pressing is only a tool, one of many that are utilized in the development of an athlete's physical abilities. Using it poorly will only yield poor results.

Instead of me simply ranting about this topic, I thought it would be better to bring on someone who is inside baseball culture itself to help discuss the topic. Scott Michael Colby, MA, CSCS is currently an Instructor on Faculty at McKendree University (Lebanon, IL), a former Head Strength and Conditioning Coach and Director of Player Development for the Puget Sound Collegiate League (Lacey, WA), a former Head Assistant and Pitching Coach for the Kitsap BlueJackets of the West Coast League (Silverdale, WA), and has contributed in the past to the Volt Blog by releasing his research on grip strength and batting power. I approached him with my questions about baseball’s complex relationship with the bench press.

Why does the bench press have such a negative stigma in baseball culture?

SMC: To understand the relationship between baseball and the bench press, you first have to understand baseball culture and history. Baseball is a sport rich in tradition and numbers, which is at the core of its allure to those of us that have a white-hot passion for the game. And conservative thinking quite often accompanies a culture with deeply entrenched traditions, though the numbers have supported innovations in the sport throughout the years. I can remember baseball coaches telling me throughout the 1980s how devilish weight training was as it would “make you muscle-bound.” (Keep in mind, the pre-game team static stretch was considered a best practice during this period of time, too.) This was the standard and a sign of the times; it doesn’t mean that these guys had bad intentions, were bad coaches, or were misinformed. It’s just where the scientific foundation of exercise science and sport performance was at that period in time.

The Steroid Era in baseball began in the 1990s and a paradigm shift in baseball strength and conditioning took place. Baseball players started seeing the benefits of the weight room. A whole new industry was born after athletes and coaches drew a correlation between weight room gains and enhanced on-field performance. Even if a significant percentage of these performance gains were chemically enhanced during this period of time, the foundation was set for today’s baseball strength and conditioning profession. Now used by many innovative baseball organizations as a holistic approach to player development, the industry standard involves strength and conditioning, nutrition, and sport psychology to enhance sport-specific coaching. The plight of the bench press in baseball is one that mirrors the evolution of strength and conditioning in baseball.

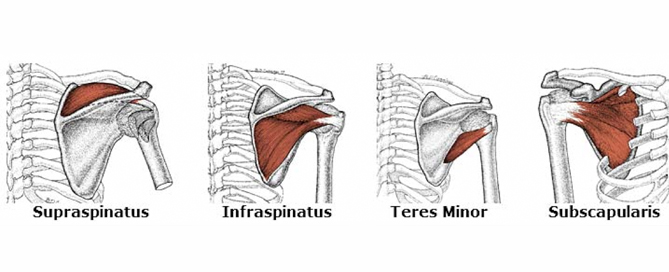

An image of a baseball athlete with tight and/or overdeveloped anterior chest/shoulder muscles on the right side. Notice how his right shoulder lifts up and off the table. Anterior/posterior imbalances like these can be caused by an incorrect push-to-pull movement ratio.

While the importance of the rotator cuff muscles and pulling actions related to the overhead throwing athlete are understood, the function of the bench press has been discouraged in baseball due to a simple misconception: the bench press will cause pectoral tightness resulting in an anterior or forward roll of the humeral head in the shoulder girdle, and thus will limit and/or alter shoulder range of motion and produce a potentially injurious situation. While this would be of dire concern if we were training our overhead throwing athlete to compete in the World Bench Press Championships, to consider the alternative (not including the pressing motion at all) would be equally extreme. This does not have to be the case and ultimately presents two ends of the bench press in baseball spectrum. Let’s put it this way: if you were to complete a program that only involved pulling motions and no pushing motions, then you would create an anterior-posterior asymmetry, putting you at just as much risk of injury as that World Bench Press Championship workout program. Think about it, and the common sense principle applies!

Alternatively, why is the bench press so popular in general fitness?

SMC: The origin of the bench press lies in the military beginnings of weight training itself. Before our sport-driven society existed, training the soldier for combat was the primary focus of physical training methods. From this beginning came a series of movements and exercises beneficial to the soldier. The pushing motion of the hands is a very important defensive action for fending off would-be attackers. It is from this motion that the bench press evolved. Through the years, the bench press has become an exercise that is relatively easy to teach and requires basic equipment that can be purchased at a reasonable cost. As a result, it has been easy for high school, college, and community facilities to include the bench press in tests and measurements (fitness testing as a primary gage of upper-body strength) and day-to-day strength and conditioning programming.

Why would an overuse of bench press be a net negative to the baseball athlete?

SMC: Hurt and injured athletes cannot typically contribute to the team on the field of play. Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is normal and appropriate rest is necessary. Movement practitioner supervision teamed with proper periodization and programming should head off any and all overuse injuries. Progressive overload is suggested so as to avoid overtraining and any subsequent overuse injuries.

Should a baseball athlete simply avoid the bench press?

SMC: No, a baseball athlete should not simply avoid the bench press as it plays an especially large part in upper-body hypertrophy and strength development. However, circumstances may exist that result in a need to modify the bench press exercise. A better way of looking at this bench press controversy is to look at the push-pull motions that oppose each other. While the pushing motion is not a prominent motion in the game of baseball, it is opposite to the pulling motion which is trained significantly so as to strengthen rotator cuff muscles associated with deceleration of the arm in the overhead throwing motion. Both push and pull motions should be incorporated within a strength and conditioning program so as to provide anterior-posterior balance and prevent anterior-posterior asymmetry in the upper trunk or thorax.

The muscles of the rotator cuff act to help decelerate forward movement of the arm, like at the end of the throwing motion.

Do the risks outweigh the rewards?

SMC: No, the risks do not outweigh the rewards where the bench press in baseball strength and conditioning is concerned. If workouts are periodized and programmed correctly, then the bench press and/or a variation of the pressing motion should be incorporated within the baseball strength and conditioning program so as to balance prescribed pulling exercises.

When would a baseball player actually need to concern themselves with bench pressing and injury risk?

SMC: Anytime that a baseball player is sore (chronically), hurt, or injured, his capacity for strength training should be reviewed by appropriate strength and conditioning and/or sport medicine personnel. Additionally, maximum strength bench pressing is not advisable during peak intensity in-season activities, as training should typically focus on sport-specific power and/or function and/or maintenance during in-season activity. The dilemma that exists in baseball strength and conditioning programming revolves around periodization complications, due to the fact that a typical baseball schedule involves a spring championship season, a competitive or developmental summer baseball season, and a developmental fall ball season. This dilemma presents a dynamic that limits the period or block of time and the duration in which hypertrophy and maximum strength can be developed in typical off-season strength training activities.

How can the bench press be modified?

A Barbell Floor Press is one way that Volt programs the bench press for baseball, softball, and other overhead atheltes, in order to modify the high shoulder demands of the full bench press movement.

SMC: The bench press can be modified in a number of ways. The pushing movement pattern typically progresses from simple to complex in level of difficulty in the following sequence: modified planking, planking, modified push-up, push-up, flies (cable, dumbbell, or machine), machine bench press (cable or plated), dumbbell bench press, barbell bench press, and plyometric pressing and/or pushing throws (i.e., medicine ball chest passes). Additional variations of the bench press can be seen according to the bench press surface, which can be manipulated utilizing a flat bench, decline bench, incline bench, and/or physio ball apparatus. Some band resistant programs, like Crossover Symmetry and J-Bands, involve standing versions of the fly and press exercises. Finally, grip and/or hand width can be manipulated from wide to narrow throughout each of the progressions listed above in order to affect the primary muscle groups worked.

What does an overuse of bench press look like in a strength and conditioning program?

SMC: Upper Crossed Syndrome (UCS) is the physical condition that most detractors of the bench press associate with baseball strength and conditioning programs that integrate the exercise. Not too dissimilar to what “Female Adolescent Texting Syndrome” or “F.A.T.S,” or “Lower Quarter Crossed Syndrome” (as documented in Anatomy for Runners by Jay Dicharry, MPT, SCS) is to runners, UCS is an anterior-posterior imbalance that is detrimental, especially to the baseball athlete. Typically associated with a sedentary lifestyle and flexion-based injuries, UCS involves a tight pectoralis, tight upper trapezius and levator scapula, weak rhomboids and lower trapezius, and weak cervical flexors. Anterior and/or forward roll of the shoulders and a forward positioning of the head (in contrast to a normal lateral alignment of the ear, shoulder, hip, and ankle) are the most common postural indicators of UCS, and shoulder impingement, neck pain, jaw pain, and/or headaches are symptoms that often accompany UCS.

How can we identify if an athlete needs to use a modification of the bench press?

SMC: As is the case especially with the more technical Olympic lifts, a functional movement pattern, a level of base strength, and proper lifting mechanics must be achieved before progressing to more complex loaded exercises. As the bench press is concerned, base functional pressing and/or pushing strength and proper bench press technique should be demonstrated prior to a baseball athlete’s participation in hypertrophy or maximum strength phases of a periodized program that incorporates dumbbell or barbell exercises. Youth level programming should also take both chronological and training age into consideration as epiphyseal injury prevention is paramount to healthy motor development. Put simply, always emphasize quality over quantity! If there is a lack of quality movement or functional strength, then consider modification.

If the bench press is done right, is there any risk?

SMC: There is risk associated with anything and everything in life. The integration of the bench press in baseball strength and conditioning programming actually provides anterior-posterior symmetry (to counter all of those pulling exercises our overhead throwing athletes do), and allows strength development in preparation for power transfer. Instead of measuring our manhood in the game of baseball by our one repetition maximum on the bench press, we should measure our player developmental level via the five tools (the ability and skill to hit for contact, hit with power, run, catch and throw) with an on-field focus. Let’s keep the bench press in the weight room as just one of the many components that involve sweat equity via training to enhance on-field performance, but let’s not just abandon the bench press altogether. As noted above, balance is key!

This article doesn’t just concern baseball players. Using the bench press to develop upper body strength is near universal in Volt programming. Does it mean Volt is strictly a bench press company hell-bent on making athletes bench three days a week? No. Every tool has its purpose, and the bench is a very good indicator of upper body strength capabilities. It’s remarkably easy to learn (you get to lie down, for crying out loud!) and can be done in probably 90% of all training facilities. Unfortunately, those same reasons give it a bad reputation. Its ease and availability make it probably the most performed lift of all time. Everybody and their uncle knows what a bench press is and is happy to tell you about it. Its familiarity and popularity lend to athletes caring too much about how much weight they can press.

As Scott said, balance is key. It is less a matter of should you or shouldn’t you perform a lift, and more a matter of why and how are you performing a lift. Anything done too frequently can lead to an overuse of the movement and begin to affect other movement qualities. The bench press is a typical culprit of overuse due to its familiarity, ease of learning, and wrongful connection to ego. Do not vilify a specific movement simply because others are performing it incorrectly or too often.

Join over 1 Million coaches and athletes using Volt's intelligent training app. For more information, click here.